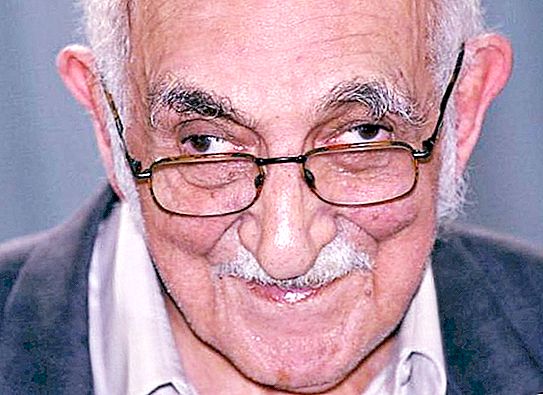

Orientalist, philosopher, philologist, writer and founder of the semiotic school Pyatigorsk Alexander Moiseevich was born in Moscow in 1929. During the war he was evacuated to Nizhny Tagil. He graduated from Moscow State University (Faculty of Philosophy), taught for several years in Stalingrad in high school, and since 1956 he worked at the Institute of Oriental Studies under the leadership of Yu. N. Roerich, where he defended his dissertation on the history of medieval literature. Next Pyatigorsk Alexander Moiseevich studied semiotics, participated in research at the University of Tartu.

Biography, books

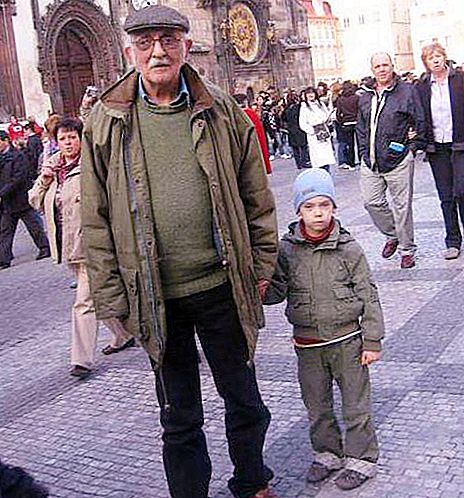

The hometown for Alexander Pyatigorsky has always remained Moscow, the city in which he was born on January 30, 1929. His family was educated and intelligent, the boy was given an excellent upbringing. Father, a prominent steel engineer, had many years of internship in Germany and England in the direction of the USSR government. The family spent the war in Nizhny Tagil, where at the age of eleven Alexander Pyatigorsky began working at the plant.

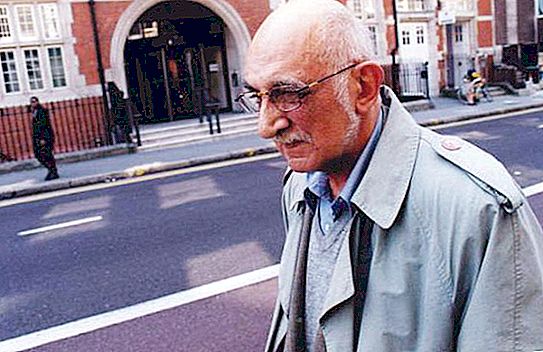

In 1951 he graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow State University and was sent to Stalingrad, where he taught at the school. In 1973 he left the country, settling in England, where he lectured at the University of London and took part in various television and radio programs. He wrote several art books and published an incredible number of collections of his own scientific articles. The main works of art are listed below.

- "The philosophy of one lane." London, 1989.

- "Remember the strange man." Moscow, 1999.

- "Stories and Dreams." Moscow, 2001.

- "Ancient man in the city." Moscow, 2001.

- "Thinking and observation." Riga, 2002.

- "An ongoing conversation." Moscow, 2004.

- "Free philosopher of Pyatigorsk." SPb, 2015.

A family

The father of the philosopher Pyatigorsky is Moses Gdalevich, a Soviet nominee, a techie who knew everything about metals and steel, taught at a university, studied science and practice, and gained experience at factories in Germany and England. By the way, no one in the family, including Moses Pyatigorsky himself, was ever repressed, despite his origin, social status, nationality (Jews) and a long stay abroad. This man was very healthy in life, only six months did not live to be a hundred years old. Compared to his father, Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky died young. Date of birth and date of death are eighty-one years apart. Mother was not from scientists, but from a family very famous for its wealth, but also, according to Alexander Moiseevich, “died young” - she was only eighty-seven.

Social activity

Since 1960, his books began to be published, at first in co-authorship (however, co-authorship often arose throughout the rest of his life). Pyatigorsky Alexander Moiseevich was actively involved in human rights activities, in the 70s he participated in rallies supporting the dissident movement, including its participants - Ginzburg, Sinyavsky, Daniel. In 1973 he managed to emigrate to Germany, then to the UK. With perestroika, Pyatigorsky Alexander Moiseevich began to receive awards from the country, which he left about thirty years ago (A. Bely prize for the novel “Remember a Strange Man, ” prize of the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences).

He knew languages, especially rare, for example Sanskrit, as well as the dialects of Tibet, and translated Buddhist and Hindu sacred texts. He has written several novels and many scientific works in this area. He lectured on subjects of political philosophy almost all over the world, being a professor at the University of London. He starred in the movie “Butterfly Hunt”, “The Philosopher Escaped”, “Clean Air of Your Freedom”, “Hitler, Stalin and Gurdjieff”, “Chantrap”. Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky died in London in 2009 from heart failure.

Buddhism

“Nobody needs a philosophy, that’s its value, ” said Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky. “That’s why it is worthy of the most intimate and long-lasting human attachments.” Two years before his death, the writer visited Moscow, where for two weeks he gave a lecture course on Buddhist philosophy at the Russian Economic School. Listeners learned a lot. About how the Buddhist consciousness and natural sciences are whimsically combined.

Alexander Moiseevich devoted many lectures to India. It was here that mathematics was improved: they came up with the positional nature of calculus, introduced zero in use. However, the Indians do not have their own schools of natural sciences, since the direction of their consciousness, which deeply comprehends linguistics, psychology, mathematics, is very different from, for example, the same ancient Greeks of the times of Aristotle. They were not so interested in arranging the internal organs of humans and animals. Also, they were not much occupied by the components of mountains, swamps and the jungle. Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky, whose philosophical views are very clearly outlined in these interesting lectures, believed that no culture should be engaged in anything alone, since this would inevitably lead to the degeneration of the nation.

Down with inertia!

The philosopher Alexander Pyatigorsky, whose biography is closely connected with the study of Tibetan teachings, examines in detail the system of scientific knowledge of the natural world in Buddhism. From the point of view of Tibetan lamas, widely educated, knowing many dialects of their language, as well as Sanskrit, Mongolian, Chinese, English, who have read many scientific books, even Darwin, despite his genius, is extremely intellectually undeveloped. But the very same British physicists and mathematicians were close to the llamas, and their intelligence received the highest praise from their lips.

European philosophers and historians, despite the fact that they were all excellent scholars, were also recognized as mediocre personalities. Development, as the philosopher Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky understands, consists primarily in freedom: firstly, the ability to find one's own answer to a question or one’s own solution to a problem, and secondly, one’s ability to immediately abandon a found option in favor of a new one. That is, to reject the entire world communal and collective inertia. Modern genetics, mathematicians, and physicists have also begun to gradually come to such a worldview.

Preset conditions

Alexander Pyatigorsky, whose biography includes numerous travels with the study of various ontological postulates, believed that it was in the seventeenth century that all European, including natural, sciences entered their new and more favorable period for discoveries. A natural scientist, as a scientist, is initially not free, his research is usually constrained by a huge number of things set by nature, and therefore he most often begins to "dance from the stove."

And philosophers are free, nothing set limits them, and they can begin knowledge from any point they want. In addition, the centuries-old established axioms do not put pressure on philosophers, since the subject as such, even at universities, has not been studied. Including antique schools of philosophy.

Becoming

Philosophy among European thinkers was understood as law, theology, later biblical studies, Hebrew and Latin (as a real language that was widely used up to the Renaissance). Medicine has been added to this set over time. All these sciences are humanities, but there was no pure philosophy among them; it was formed in the New Age. Only in the second half of the eighteenth century did the first department of academic philosophy appear in Edinburgh. D. Hume and A. Smith fought for a place on it. And then went Kant, Fichte, Hegel, after which finally philosophy took shape as an object of study. But Buddhists have always philosophized, as Alexander Pyatigorsky explained in his lectures. This was the basis of their education.

Not science

Pyatigorsky Alexander Moiseevich, whose books are mainly devoted to philosophy, did not get tired of saying that it is not in the list of full-fledged sciences. He was convinced that philosophy was not a science at all. “In the pantheon of sciences, ” he wrote, “there is no hierarchical vertical; rather, it is a certain volume or space filled not with anything, but with culture. That’s where philosophy takes some place …”

In the end, without philosophy, humanity can survive perfectly. This cannot be said, for example, about medicine.

What about math? What about physics?

Even physics, the need for which arises only at a certain turn of consciousness, when both the meaning and the significance of what it brings to people are exaggerated, is not so necessary for humanity as is commonly believed. The final theory is also impossible in physics, since the process of thinking in man cannot be final. Pyatigorsk Alexander Moiseevich, whose biography consisted of "constant reflection and reflection on reflection", I am sure that the final theory, which so many scientists so eagerly develop, is a tomfoolery reminiscent of creating an absolutely fair, final and global society. Mankind has repeatedly paid dearly for this utopian idea (communism, for example), but people will never succeed in achieving an idyll. The pursuit of the unattainable shows that humanity is not only not at the top of its intellectual capabilities, but, on the contrary, closer to the beginning, as it continues to start up obviously impracticable enterprises. According to the philosopher, this is not bad, but excellent, since the most important criterion for correctness is that where to go, that it is interesting along the way.

Exposure of postulates

An uneducated person, according to Pyatigorsky, may be a philosopher, but this is extremely unlikely. No interesting thinking starts from scratch. And without his own philosophy, a person cannot engage in any philosophy. Pyatigorsk Alexander Moiseevich, whose wives all loved him extremely, before admiration, nevertheless refuses the beautiful half of philosophical abilities.

As the hero of our article reasoned: women, in his opinion, are much more difficult to do useless work, and philosophy is absolutely useless. However, it is far from characteristic of men for everyone. This is generally a rare thing - among women, and among men, and among crocodiles. To do this, one must be abnormal, as, for example, when a person buys sweets for the last money, and not bread. Philosophy is the pursuit of the nonexistent, which is better than just good. And the fact that a person should be happy is an irresponsible phrase and extremely harmful. Perhaps one of the few real tasks of the philosopher is to destroy the general postulates of such a plan.

Linguistics and semiotics

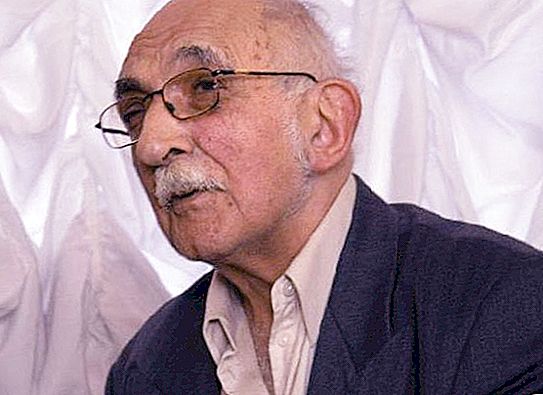

Regarding scientific education, Pyatigorsky wrote and spoke extremely interesting. For example, like that. The philosopher primarily reflects on the language, his own and the interlocutor, therefore, philosophy is in very close contact with both sociology and linguistics. Many speakers start their speech with the words: "it is obvious that …" or "everyone knows that …". This is a lie. Nothing is obvious. It all depends on the momentary nature of our “want-not want”. It’s normal for a person to not think and know nothing. None of this has died. Who, for example, now remembers the great linguists from the world famous Moscow Nest? Normal Russian people do not know a single surname: Starostin, Klimov, Yakovlev, Polivanov, Abaev … And in the West, Russian linguists are extolled. Everyone there knows Jacobson, the Reformed, and Zaliznyak. There are museums dedicated to these people who rethought the Russian language. Many lectures that Alexander Moiseevich Pyatigorsky gave at Russian universities devoted to these problems. A photo of some meetings with students is attached.

Alexander Pyatigorsky was engaged in semiotics exclusively as a philosopher. Although he did not have his own theory in this area, he used it as a tool to help solve problems in the neighboring sciences. He believed that, like philosophy, it is useless, since semiotics is a pure theory, but in the sciences there is something more useful and applied: the rules of practical conclusion, forecasting, experiment. He immediately specified that semiotics can help to reflect in any field.

About language and leisure

Most of all Pyatigorsk was upset by the abundance of jargon in the speech of both Russian and English students. Moreover, those whose parents are highly educated people who were brought up on literary heroes. And it turns out that the language, say, in Russia is best preserved among the children of semi-educated people - factory chief mechanics or artillery majors.

He sees the degeneration of the language, not coming from below, but from the very top, including from university professors, and gives numerous examples from his own experience. Philosophers are usually people who have leisure. The best thinkers come from those who had a lot of free time. The same applies to culture and science, which also cannot be made true on the run. Need a carriage of the past, not a modern superjet.